We are pleased to invite our wonderful friend Jill – Director of Adventure Play at The Parish School in Houston, Texas to guest write on our blog about Playwork and Libraries. Her fascinating experiences comes from an unusual pairing, but one that really works. Thank you so much for sharing with us!

Next weekend, I will present playwork and child-directed play to a room full of librarians and early childhood educators. For a number of reasons, I’m really excited about playwork and libraries.

First, this room of people will bridge my two professional worlds, which is not something I commonly get to experience. I run a site-based adventure playground at a school in Houston, Texas. I identify as a playworker, someone with training in the UK-based professional model that supports child-directed play. Often on adventure playgrounds, but also in hospitals, after school clubs, at recess, and in the forest.

Being a school librarian

I am also a school librarian, at the same school, and have the privilege of working with children. In short, ages 5-12 for 45 minutes weekly, as they:

- explore the shelves;

- build a relationship to literature, and;

- seek answers to their bazillions of amazing and excellent questions.

A lot of people think these two worlds don’t go together because of the way the two spaces look.

Libraries with rows of neatly shelved books, categorized by fiction and nonfiction, by author’s last name, by Dewey Decimals. And adventure playgrounds, where children make their own decisions about how to spend their time and where to put things.

In a library, you can get on a computer and often find out exactly where a book is located using an OPAC (Online Public Access Catalog). On an adventure playground, you have to find the kid who last used a hammer and hope they’re willing to give you directions to where they dropped it.

But libraries succumb to design because the categories and order make books accessible. And adventure playgrounds receive design for children because that is what makes them accessible. The two spaces have something deeper in connection than their appearance or system of organization. They are both environments that support freedom and exploration as defined by the individual, at the moment. They both meet people where they need to be met.

Playwork and libraries = great memories

Second, many of my favourite childhood play memories happened in the library, so I have a lot to say about the topic. Starting around Kindergarten, my mom would take my brother and me to our neighbourhood public library, set up shop at a table, give us a kiss on the forehead and expect to see us a couple of hours later.

I remember, for instance, starting in the picture books. Usually with Bill Peet, Bread and Jam for Francis, stuff I could find in my classroom at school. Then wandering into the nonfiction section.

I would pull a book about stars and planets off the shelf, look at the pictures, want to learn more, and right next to the space book there were other space books! Oh, but nearby was the animal section and that area was the biggest in the nonfiction area. Marsupials aren’t just kangaroos, there are wombats and koalas, and there’s even one that flies with a baby in its pouch called a sugar glider. Why are there so many animals with baby pockets in Australia? Better go find a book about Australia.

Pretending

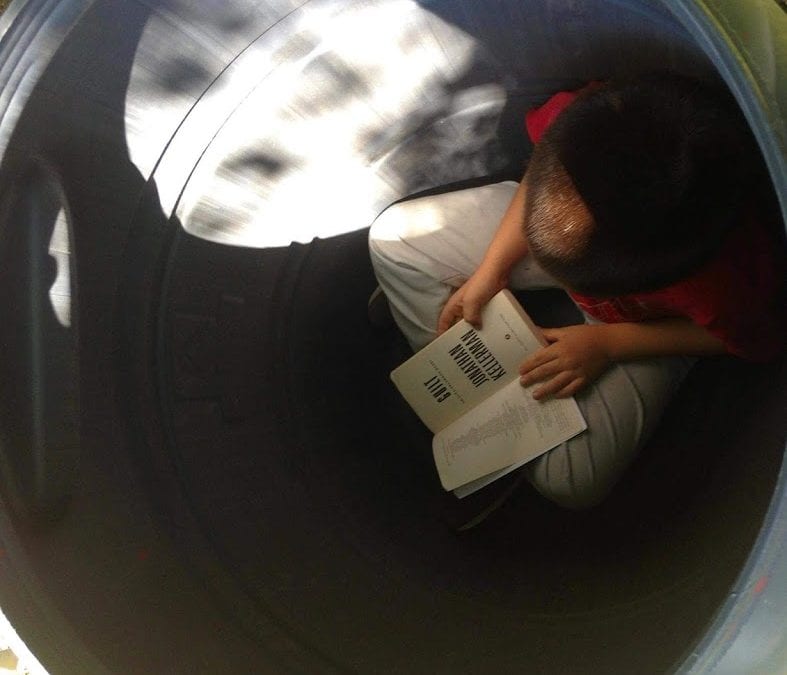

Sometimes I would pretend to read books my older brother read, The Great Brain series or A Swiftly Tilting Planet. I could just hold them up to my face and people thought I was reading them. And then there was the adult section. So much naughty stuff, right there without supervision. The Robert Mapplethorpe book in the art section was a thing of legend, its location passed from child to child.

I would collect up piles of books and curl up on the cushion at the base of the bubble window in the children’s area. Sometimes I saw friends from school, and often I had conversations with adults – a college student wanting a break, a homeless person needing to tell a story, a welcoming librarian named Judy, who had very straight hair she wore in a bob. Just like a playworker, when Judy saw me in the adult section looking at anatomy texts, she kept walking past without a glance or a judgment. And when I told her the things I discovered about Australia or space, she always listened as if I were telling her the most interesting thing she’d heard all day.

Child-directed play in libraries

Finally, there should be more child-directed play opportunities in libraries. I believe this, because libraries are community centres and communities need play. Playworkers and librarians have quite a lot in common:

- Both are service professions;

- The two provide tools for accessibility;

- Both trust individuals to self-determine and self-direct their activities and because of this, both provide environments for identity to be explored and found;

- Both protect individuals from censorship, even when it’s difficult or uncomfortable;

- These roles are ethically bound to protect human rights (right to play, right to intellectual freedom and privacy);

- Both have to balance all of the above against the same rights of others, within a shared space;

- Moreover, they respond to challenges by providing more options and changing the environment, rather than restricting access;

- Both take guidance from a series of principles. But they cater to the needs of a particular community, making every library or play space unique.

And both librarians and playworkers are adept at defending all of the above, because pleasure reading and play are suspect in a culture that values activities with predetermined purpose and measurable goals. The internal journeys we take on the playground and through the pages of books define who we are, and who we would like to become, but they are the first to go when cuts are made to funding or time is short in a day.

Librarians are motivated

So we librarians do studies to show that intrinsic motivation is an essential component of literacy, and we playworkers lean on compound flexibility to justify the child-made nature of our adventure playgrounds, but we both know that our goal is to create spaces where people can experience what they are driven to experience, when they are driven to experience it.

“It’s funny that we think of libraries as quiet demure places where we are shushed by dusty, bun-balancing, bespectacled women. The truth is libraries are raucous clubhouses for free speech, controversy and community. Librarians have stood up to the Patriot Act, sat down with noisy toddlers and reached out to illiterate adults. Libraries can never be shushed.” – Paula Poundstone, “United for Libraries Forms National Partnership with Paula Poundstone”, American Library Association, July 2, 2009. (Accessed November 3, 2019)

By Jill Wood